Chinese Students Abroad Face Pressure to Spy

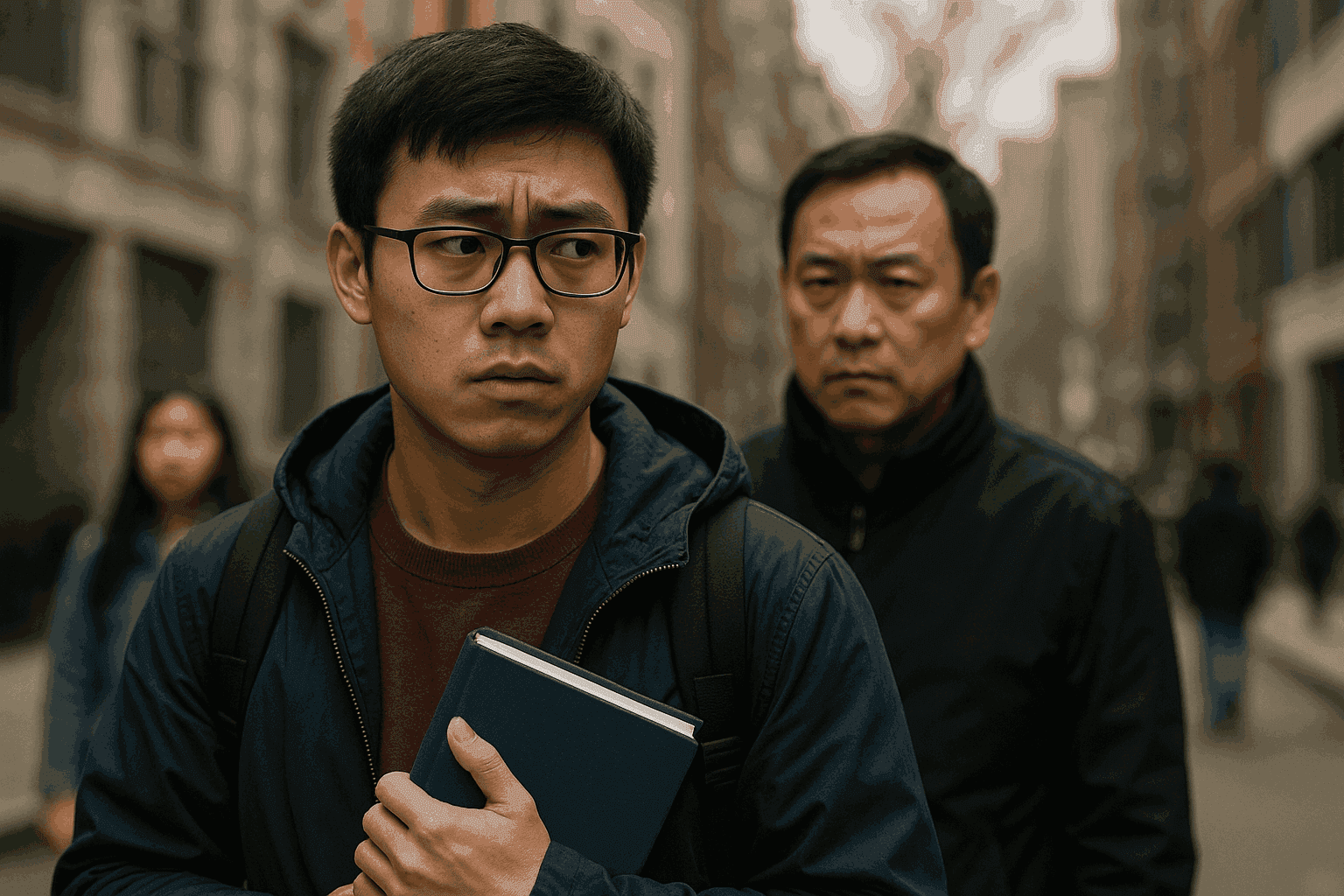

When Li Wei arrived at a top British university to pursue his master's degree, he thought he had left the political pressures of home behind. But not long after settling into campus life, a message popped up on his phone from an unfamiliar number.

It was someone from back home, a "liaison", asking him to keep an eye on events at his university and to "report anything that could harm the motherland's image.”

Li's story isn't unique. A recent report by UK‑China Transparency, a monitoring group that tracks Beijing's influence abroad, has uncovered a troubling trend:

Chinese university students are being asked, or subtly coerced, to spy on their classmates and professors. The goal? To flag discussions and activities that the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) might find politically sensitive.

For many, this is more than just uncomfortable. It's a clash between the promise of academic freedom and the long arm of state control that follows them overseas.

A Whisper Network of Student Informants

The UK‑China Transparency report, released on 4 August 2025, is based on testimonies from professors and students across British universities.

Several academics reported that Chinese students had confided in them, expressing fear and confusion after being contacted by officials, sometimes before even leaving China, and often again after returning home for visits.

Some students were bluntly asked to monitor campus events. Others were told to "pay attention" to certain classmates who were vocal about sensitive topics like Taiwan, Hong Kong, or human rights.

"The surveillance is everywhere," one professor said. "Students feel like they're always being watched, even by their peers.”

China's embassy in the UK has dismissed these claims as "groundless." But for students like Li, the pressure feels very real.

The Subtle Machinery of Coercion

For years, China has operated systems of "student information officers" within its universities, peer informants who monitor classmates and report on dissent. Now, it seems, that same model is being exported to foreign campuses.

Often, the students targeted abroad are recipients of government scholarships through the China Scholarship Council (CSC).

These scholarships, while prestigious and valuable, come with unspoken expectations. Regular check-ins with consulate "handlers" are common.

At these meetings, students are expected to discuss their academic work, but also report on peers who may have expressed controversial opinions.

If students hesitate or refuse, consequences can follow. Some report subtle warnings about their family's safety back home.

Others speak of scholarship funding being suddenly "reviewed." One student, under the condition of anonymity, recalled being told, "You're either with the motherland, or you're against it.”

This blending of academic espionage and personal coercion creates a chilling effect on campuses, where free inquiry is supposed to flourish.

The Human Cost: Self-Censorship and Fear

For many Chinese students abroad, university life has become a careful balancing act. Speaking out on sensitive issues, even in a casual classroom discussion, could have repercussions that extend far beyond graduation.

"It's not just about spying," Li says quietly. "It's about silencing. They want you to feel like you're never really safe to speak your mind.”

Professors are also feeling the impact. Several UK academics reported being harassed by visiting Chinese scholars. Some were warned during lectures that their teachings were "being monitored." Others received vague messages suggesting that their families in China should "stay safe.”

These subtle acts of intimidation have led some educators to avoid sensitive topics altogether. "The risk isn't just theoretical anymore," one professor said. "It's personal.”

Universities Caught in the Middle

British universities find themselves in a difficult position. On one hand, they are committed to free speech and academic openness.

On the other hand, many are financially dependent on Chinese student' tuition, which can account for a large portion of their revenue.

This financial reliance often makes university administrators cautious about taking a firm stance. Some prefer to downplay the risks, worried about straining relationships with Chinese institutions and government-linked scholarship programs.

The UK's higher education regulator, the Office for Students (OfS), has urged universities to address these concerns head-on.

New guidelines encourage institutions to assess foreign partnerships more rigorously and ensure students are protected from coercive pressures. But enforcement remains tricky.

Echoes Across the Atlantic: The U.S. Experience

The UK isn't alone in facing this problem. In the U.S., multiple investigations, including reports by Stanford University and The Washington Post, have highlighted similar patterns of Chinese students under pressure to spy on their peers.

The Chinese National Intelligence Law of 2017 mandates all citizens, even those abroad, to assist state intelligence agencies when called upon.

For students, this translates into regular consulate visits, reporting requirements, and a lingering fear that saying "no" could cost them their future.

While many students resist these pressures, the very existence of these tactics creates an atmosphere of fear and self-censorship. The classroom, once a sanctuary for free thought, becomes another space where words are carefully measured.

Beyond Students: A Global Surveillance Machine

The use of student informants abroad is just one part of China's broader surveillance ecosystem. Domestically, the state's use of video monitoring.

AI-driven data analytics and citizen-reporting apps are well-documented. Initiatives like the "Chaoyang Masses", in which ordinary citizens were enlisted to watch for "unpatriotic behavior"- show how deeply embedded these practices are in daily life.

Now, these tactics are stretching beyond China's borders, reshaping the dynamics of academic exchange worldwide.

What Comes Next?

Universities are at a crossroads. Do they prioritize open academic collaboration, or do they tighten scrutiny over foreign-funded programs that may compromise research integrity and personal freedoms?

Some are already reassessing partnerships with Confucius Institutes and scrutinizing CSC scholarships. Others are pushing for more nuanced approaches, ones that protect students from both espionage recruitment and rising anti-Chinese sentiment.

The conversation is delicate. "We cannot afford to treat every Chinese student as a spy," warns one policy expert. "The vast majority are here to learn, to grow, to exchange ideas. But we must acknowledge that some are being put in impossible situations by their own government.”

For students like Li Wei, the hope is simple. "I just want to be a student again," he says. "Not an informant. Not a target. Just a student."

About Author

Let us help you yield your true academic potential for foreign education. To configure and discover an apt international enrolment strategy, get in touch!

- +923041111444

- info@edify.pk

- Edify Building, 3rd Floor, Madina Town Faisalabad

© 2026 Edify Group of Companies. All Rights Reserved.